- Home

- Joanne Harris

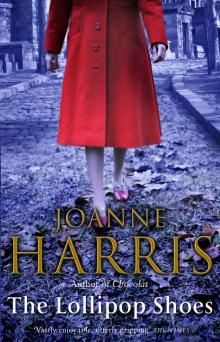

The Lollipop Shoes

The Lollipop Shoes Read online

About the Book

‘Who died?’ I said. ‘Or is it a secret?’

‘My mother, Vianne Rocher.’

Seeking refuge and anonymity in the cobbled streets of Montmartre, Yanne and her two daughters live peacefully, if not happily, above their little chocolate shop. Nothing unusual marks them out; no red sachets hang by the door. The wind has stopped – at least for a while. Then into their lives blows Zozie de l’Alba, the lady with the lollipop shoes, ruthless, devious and seductive.

With everything she loves at stake, Yanne must face a difficult choice; to flee, as she has done so many times before, or to confront her most dangerous enemy . . .

Herself.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Part One: Death

1. Wednesday, 31st October – Día de los Muertos

2. Wednesday, 31st October

3. Wednesday, 31st October

4. Wednesday, 31st October

5. Thursday, 1st November – All Saints

Part Two: One Jaguar

1. Monday, 5th November

2. Tuesday, 6th November

3. Thursday, 8th November

4. Thursday, 8th November

5. Friday, 9th November

6. Friday, 9th November

7. Friday, 9th November

8. Saturday, 10th November

Part Three: Two Rabbit

1. Wednesday, 14th November

2. Thursday, 15th November

3. Friday, 16th November

4. Saturday, 17th November

5. Monday, 19th November

6. Monday, 19th November

Part Four: Change

1. Tuesday, 20th November

2. Tuesday, 20th November

3. Wednesday, 21st November

4. Thursday, 22nd November

5. Friday, 23rd November

6. Monday, 26th November

7. Tuesday, 27th November

8. Wednesday, 28th November

9. Saturday, 1st December

Part Five: Advent

1. Saturday, 1st December

2. Saturday, 1st December

3. Sunday, 2nd December

4. Monday, 3rd December

5. Tuesday, 4th December

6. Tuesday, 4th December

7. Wednesday, 5th December

8. Thursday, 6th December

9. Thursday, 6th December

10. Friday, 7th December

11. Saturday, 8th December

12. Sunday, 9th December

Part Six: The Kindly Ones

1. Monday, 10th December

2. Tuesday, 11th December

3. Wednesday, 12th December

4. Thursday, 13th December

5. Friday, 14th December

6. Friday, 14th December

7. Saturday, 15th December

8. Saturday, 15th December

9. Sunday, 16th December

10. Monday, 17th December

11. Tuesday, 18th December

12. Tuesday, 18th December

Part Seven: The Tower

1. Wednesday, 19th December

2. Wednesday, 19th December

3. Thursday, 20th December

4. Friday, 21st December – Winter Solstice

5. Friday, 21st December

6. Friday, 21st December

7. Saturday, 22nd December

8. Saturday, 22nd December

9. Sunday, 23rd December

Part Eight: Yule

1. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 11.30 a.m

2. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 3.00 p.m

3. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 4.30 p.m

4. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 5.20 p.m

5. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 6.00 p.m

6. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 7.00 p.m

7. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 8.30 p.m

8. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 10.30 p.m

9. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 10.40 p.m

10. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 10.55 p.m

11. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 11.00 p.m

12. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 11.05 p.m

13. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 11.05 p.m

14. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 11.15 p.m

15. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 11.25 p.m

16. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 11.30 p.m

17. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 11.30 p.m

18. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. 11.35 p.m

19. Monday, 24th December – Christmas Eve. Midnight

Epilogue: Tuesday, 25th December – Christmas Day

About the Author

Also by Joanne Harris

Copyright

The Lollipop Shoes

Joanne Harris

To A. F. H.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Once again, heartfelt thanks to everyone who helped guide this book from babysteps to walking in heels. To Serafina Clarke, Jennifer Luithlen, Brie Burkeman and Peter Robinson; to my fabulous editor Francesca Liversidge; to Claire Ward for her wonderful cover design; to my terrific publicist Louise Page-Lund and to all my friends at Transworld, London. Many thanks also to Laura Grandi in Milan and to Jennifer Brehl, Lisa Gallagher and everyone at HarperCollins, New York. Thanks too to my PA, Anne Riley; to Mark Richards, for running the website; to Kevin, for running everything else; to Anouchka, for enchiladas and Kill Bill; to Joolz, Anouchka’s evil aunt, and to Christopher, Our Man in London. Special thanks go to Martin Myers, super-rep, who saved my sanity this Christmas, as well as to all the loyal reps, booksellers, librarians and readers who ensure that my books are still kept on the shelves.

PART ONE

Death

1

Wednesday, 31st October

Día de los Muertos

IT IS A relatively little-known fact that, over the course of a single year, about twenty million letters are delivered to the dead. People forget to stop the mail – those grieving widows and prospective heirs – and so magazine subscriptions remain uncancelled; distant friends unnotified; library fines unpaid. That’s twenty million circulars, bank statements, credit cards, love letters, junk mail, greetings, gossip and bills, dropping daily on to doormats or parquet floors, thrust casually through railings, wedged into letter-boxes, accumulating in stairwells, left unwanted on porches and steps, never to reach their addressee. The dead don’t care. More importantly, neither do the living. The living just follow their petty concerns, quite unaware that very close by, a miracle is taking place. The dead are coming back to life.

It doesn’t take much to raise the dead. A couple of bills; a name; a postcode; nothing that can’t be found in any old domestic bin-bag, torn apart (perhaps by foxes) and left on the doorstep like a gift. You can learn a lot from abandoned mail: names, bank details, passwords, e-mail addresses, security codes. With the right combination of personal details you can open up a bank account; hire a car; even apply for a new passport. The dead don’t need such things any more. A gift, as I said, just waiting for collection.

Sometimes Fate even delivers in person, and it always pays to be alert. Carpe diem, and devil take the hindmost. Which is why I always read the obituaries, sometimes managing to acquire the identity even before the funeral has taken place. And which is why, when I saw the sign, and beneath it the post-box with its packet of letters, I accepted the gift with a gracious smile.

Of course, it wasn’t my po

st-box. The postal service here is better than most, and letters are rarely misdelivered. It’s one more reason I prefer Paris; that and the food, the wine, the theatres, the shops and the virtually unlimited opportunities. But Paris costs – the overheads are extraordinary – and besides, I’d been itching for some time to reinvent myself again. I’d been playing it safe for nearly two months, teaching in a lycée in the 11th arrondissement, but in the wake of the recent troubles there I’d decided at last to make a clean break (taking with me twenty-five thousand euros’ worth of departmental funds, to be delivered into an account opened in the name of an ex-colleague and to be removed discreetly, over a couple of weeks), and had a look at apartments to rent.

First, I tried the Left Bank. The properties there were out of my league; but the girl from the agency didn’t know that. So, with an English accent and going by the name of Emma Windsor, with my Mulberry handbag tucked negligently into the crook of my arm and the delicious whisper of Prada around my silk-stockinged calves, I was able to spend a pleasant morning window-shopping.

I’d asked to view only empty properties. There were several along the Left Bank: deep-roomed apartments overlooking the river; mansion flats with roof gardens; penthouses with parquet floors.

With some regret, I rejected them all, though I couldn’t resist picking up a couple of useful items on the way. A magazine, still in its wrapper, containing the customer number of its intended recipient; several circulars; and at one place, gold: a banker’s card in the name of Amélie Deauxville, which needs nothing but a phone call for me to activate.

I left the girl my mobile number. The phone account belongs to Noëlle Marcelin, whose identity I acquired some months ago. Her payments are quite up to date – the poor woman died last year, aged ninety-four – but it means that anyone tracing my calls will have some difficulty finding me. My internet account, too, is in her name, and remains fully paid-up. Noëlle is too precious for me to lose. But she will never be my main identity. For a start, I don’t want to be ninety-four. And I’m tired of getting all those advertisements for stair-lifts.

My last public persona was Françoise Lavery, a teacher of English at the Lycée Rousseau in the 11th. Age thirty-two; born in Nantes; married and widowed in the same year to Raoul Lavery, killed in a car crash on the eve of the anniversary – a rather romantic touch, I thought, that explained her faint air of melancholy. A strict vegetarian, rather shy, diligent, but not talented enough to be a threat. All in all, a nice girl – which just goes to show you should never judge by appearances.

Today, however, I’m someone else. Twenty-five thousand euros is no small sum, and there’s always the chance that someone will begin to suspect the truth. Most people don’t – most people wouldn’t notice a crime if it was going on right in front of them – but I haven’t got this far by taking risks, and I’ve found that it’s safer to stay on the move.

So I travel light – a battered leather case and a Sony laptop containing the makings of over a hundred possible identities – and I can be packed, cleaned out, all traces gone in rather less than an afternoon.

That’s how Françoise disappeared. I burnt her papers, correspondence, bank details, notes. I closed all accounts in her name. Books, clothes, furniture and the rest, I gave to the Croix Rouge. It never pays to gather moss.

After that I needed to find myself anew. I booked into a cheap hotel, paid on Amélie’s credit card, changed out of Emma’s clothes and went shopping.

Françoise was a dowdy type; sensible heels and neat chignons. My new persona, however, has a different style. Zozie de l’Alba is her name – she is vaguely foreign, though you might be hard pressed to tell her country of origin. She’s as flamboyant as Françoise was not – wears costume jewellery in her hair; loves bright colours and frivolous shapes; favours bazaars and vintage shops, and would never be seen dead in sensible shoes.

The change was neatly executed. I entered a shop as Françoise Lavery, in a grey twinset and a string of fake pearls. Ten minutes later, I left as someone else.

The problem remains: where to go? The Left Bank, though tempting, is out of the question, though I believe Amélie Deauxville may be good for a few thousand more before I have to ditch her. I have other sources, too, of course, not including my most recent – Madame Beauchamp, the secretary in charge of departmental finances at my erstwhile place of work.

It’s so easy to open a credit account. A couple of spent utility bills; even an old driving licence can be enough. And with the rise of online purchasing, the possibilities are expanding on a daily basis.

But my needs extend to far, far more than a source of income. Boredom appals me. I need more. Scope for my abilities, adventure, a challenge, a change.

A life.

And that’s what Fate delivered to me, as if by accident this windy late-October morning in Montmartre, as I glanced into a shop window and saw the neat little sign taped to the door:

Fermé pour cause de décès.

It’s been some time since I last came here. I’d forgotten how much I enjoyed it. Montmartre is the last village in Paris, they say, and this part of the Butte is almost a parody of rural France, with its cafés and little crêperies; its houses painted pink or pistachio, fake shutters at the windows, and geraniums on every window-ledge; all very consciously picturesque, a movie-set miniature of counterfeit charm that barely hides its heart of stone.

Perhaps that’s why I like it so much. It’s a perfect setting for Zozie de l’Alba. And I found myself there almost by chance; stopped in a square behind the Sacré-Coeur; bought a café-croissant at a bar called Le P’tit Pinson and sat down at a table on the street.

A blue tin plate high up on the corner gave the name of the square as Place des Faux-Monnayeurs. A tight little square like a neatly made bed. A café, a crêperie, a couple of shops. Nothing more. Not even a tree to soften those edges. But then for some reason, a shop caught my eye – some kind of a chichi confiserie, I thought, though the sign above the door was blank. The blind was half-drawn, but from where I was sitting I could just see the display in the window, and the bright-blue door like a panel of sky. A small, repetitive sound crossed the square; a bundle of wind-chimes hanging above the door, sending out little random notes like signals in the air.

Why did it draw me? I couldn’t say. There are so many of these little shops along the warren of streets leading up the Butte de Montmartre, slouching on the cobbled corners like weary penitents. Narrow-fronted and crook-backed, they are often damp at street level, cost a fortune to rent and rely mainly on the stupidity of tourists for their continued existence.

The rooms above them are rarely any better. Small, sparse and inconvenient; noisy at night, when the city below comes to life; cold in winter, and most likely unbearable in summer, when the sun presses down on the heavy stone slates and the only window, a skylight not eight inches wide, lets in nothing but the stifling heat.

And yet – something there had caught my interest. Perhaps the letters, poking out from the metal jaws of the post-box like a sly tongue. Perhaps the fugitive scent of nutmeg and vanilla (or was that just the damp?) that filtered from beneath the sky-blue door. Perhaps the wind, flirting with the hem of my skirt, teasing the chimes above the door. Or perhaps the notice – neat, hand-lettered – with its unspoken, tantalizing potential.

Closed due to bereavement.

I’d finished my coffee and croissant by then. I paid, stood up and went in for a closer look. The shop was a chocolaterie; the tiny display window crammed with boxes and tins, and behind them in the semi-darkness I could see trays and pyramids of chocolates, each one under a round glass cloche like wedding bouquets from a century ago.

Behind me, at the bar of Le P’tit Pinson, two old men were eating boiled eggs and long slices of buttered bread while the aproned patron held forth at some volume about someone called Paupaul, who owed him money.

Beyond that the square was still almost deserted, but for a woman sweeping the pavement

and a couple of artists with easels under their arms, on their way to the Place du Tertre.

One of them, a young man, caught my eye. ‘Hey! It’s you!’

The hunting call of the portrait artist. I know it well – I’ve been there myself – and I know that look of pleased recognition, implying that he has found his muse; that his search has taken many years; and that however much he charges me for the extortionate result, the price can in no way do justice to the perfection of his oeuvre.

‘No, it’s not,’ I told him drily. ‘Find someone else to immortalize.’

He gave me a shrug, pulled a face, then slouched off to rejoin his friend. The chocolaterie was all mine.

I glanced at the letters, still poking impudently from the letter-box. There was no real reason to take the risk. But the simple fact was, the little shop drew me, like a shining something glimpsed between the cobbles, that might turn out to be a coin, a ring or just a piece of tinfoil as it catches the light. And there was a whisper of promise in the air, and besides, it was Hallowe’en, the Día de los Muertos, always a lucky day for me, a day of endings and beginnings, of ill winds and sly favours and fires that burn at night. A time of secrets; of wonders – and, of course, the dead.

I took a last quick glance around. No one was watching. I was sure no one saw as, with a swift movement, I pocketed the letters.

The autumn wind was gusting hard, dancing the dust around the square. It smelt of smoke – not Paris smoke, but the smoke of my childhood, not often remembered – a scent of incense and frangipani and fallen leaves. There are no trees on the Butte de Montmartre. It’s just a rock, its wedding-cake icing barely concealing its essential lack of flavour. But the sky was a brittle, eggshell colour, marked with a complex pattern of vapour-trails, like mystic symbols on the blue.

Among them I saw the Ear of Maize, the sign of the Flayed One – an offering, a gift.

I smiled. Could it be a coincidence?

Death, and a gift – all in one day?

Once, when I was very young, my mother took me to Mexico City, to see the Aztec ruins and to celebrate the Day of the Dead. I loved the drama of it all: the flowers and the pan de muerto and the singing and the sugar skulls. But my favourite was the piñata, a painted papier-mâché animal figure, hung all over with firecrackers and filled with sweets, coins and small, wrapped presents.

The Evil Seed

The Evil Seed Gentlemen and Players

Gentlemen and Players A Cat, a Hat, and a Piece of String

A Cat, a Hat, and a Piece of String Different Class

Different Class Chocolat

Chocolat Five Quarters of the Orange: A Novel

Five Quarters of the Orange: A Novel A Pocketful of Crows

A Pocketful of Crows Runelight

Runelight Runemarks

Runemarks Jigs & Reels: Stories

Jigs & Reels: Stories Sleep, Pale Sister

Sleep, Pale Sister Holy Fools

Holy Fools The Testament of Loki

The Testament of Loki Peaches for Monsieur Le Curé

Peaches for Monsieur Le Curé Blueeyedboy

Blueeyedboy The Lollipop Shoes

The Lollipop Shoes Coastliners

Coastliners Jigs & Reels

Jigs & Reels Five Quarters of the Orange

Five Quarters of the Orange