- Home

- Joanne Harris

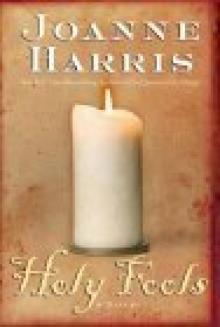

Holy Fools

Holy Fools Read online

HOLY FOOLS

Joanne Harris

To Serafina

CONTENTS

PART ONE : Juliette

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

PART TWO : LeMerle

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

PART THREE : Isabelle

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

PART FOUR : Perette

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

EPILOGUE

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Joanne Harris

Copyright

About the Publisher

Part One

Juliette

1

JULY 3RD, 1610

It begins with the players. Seven of them, six men and a girl, she in sequins and ragged lace, they in leathers and silk. All of them masked, wigged, powdered, painted; Arlequin and Scaramouche and the long-nosed Plague Doctor, demure Isabelle and the lecherous Géronte, their gilded toenails bright beneath the dust of the road, their smiles whitened with chalk, their voices so harsh and so sweet that from the first they tore at my heart.

They arrived unannounced in a green and gold caravan, its panels scratched and scarred, but the scarlet inscription still legible for those who could read it.

LAZARILLO’S WORLD PLAYERS!

TRAGEDY AND COMEDY!

BEASTS AND MARVELS!

And all around the script paraded nymphs and satyrs, tigers and olifants in crimson, rose, and violet. Beneath, in gold, sprawled the proud words:

PLAYERS TO THE KING

I didn’t believe it myself, though they say old Henri had a commoner’s tastes, preferring a wild-beast show or a comédie-ballet to the most exquisite of tragedies. Why, I danced for him myself on the day of his wedding, under the austere gaze of his Marie. It was my finest hour.

Lazarillo’s troupe was nothing in comparison, and yet I found the display nostalgic, moving to a degree far beyond the skill of the players themselves. Perhaps a premonition; perhaps a fleeting vision of what once was, before the spoilers of the new Inquisition sent us into enforced sobriety, but as they danced, their purples and scarlets and greens ablaze in the sun’s glare, I seemed to see the brave, bright pennants of ancient armies moving out across the battlefield, a defiant gesture to the sheet-shakers and apostates of the new order.

The Beasts and Marvels of the inscription consisted of nothing more marvelous than a monkey in a red coat and a small black bear, but there was, besides the singing and the masquerade, a fire-eater, jugglers, musicians, acrobats, and even a rope-dancer, so that the courtyard was aflame with their presence, and Fleur laughed and squealed with delight, hugging me through the brown weave of my habit.

The dancer was dark and curly-haired, with gold rings on her feet. As we watched she sprang onto a taut rope held on one side by Géronte and on the other by Arlequin. At the tambourin’s sharp command they tossed her into the air, she turned a somersault, and landed back on the rope as neatly as I might once have done. Almost as neatly, in any case; for I was with the Théâtre des Cieux, and I was L’Ailée, the Winged One, the Sky-dancer, the Flying Harpy. When I took to the high rope on my day of triumph, there was a gasp and a silence and the audience—soft ladies, powdered men, bishops, tradesmen, servants, courtiers, even the king himself—blanched and stared. Even now I remember his face—his powdered curls, his eager eyes—and the deafening surge of applause. Pride’s a sin, of course, though personally I’ve never understood why. And some would say it’s pride brought me where I am today—brought low, if you like, though they say I’ll rise higher in the end. Oh, when Judgment Day comes I’ll dance with the angels, Soeur Marguerite tells me, but she’s a crazy, poor, twitching, tic-ridden thing, turning water into wine with the mixture from a bottle hidden beneath her mattress. She thinks I don’t know, but in our dorter, with only a thin partition between each narrow bed, no one keeps their secrets for long. No one, that is, but me.

The Abbey of Sainte Marie-de-la-mer stands on the western side of the half-island of Noirs Moustiers. It is a sprawling building set around a central courtyard, with wooden outbuildings to the side and around the back. For the past five years it has been my home; by far the longest time I have ever stayed in any place. I am Soeur Auguste—who I was does not concern us: not yet, anyway. The abbey is perhaps the only refuge where the past may be left behind. But the past is a sly sickness. It may be carried on a breath of wind; in the sound of a flute; on the feet of a dancer. Too late, as always, I see this now; but there is nowhere for me to go but forward. It begins with the players. Who knows where it may end?

The rope-dancer’s act was over. Now came juggling and music while the leader of the troupe—Lazarillo himself, I presumed—announced the show’s finale.

“And now, good sisters!” His voice, trained in theaters, rolled across the courtyard. “For your pleasure and edification, for your amusement and delight—Lazarillo’s World Players are proud to perform a Comedy of Manners, a most uproarious tale! I give you”—he paused dramatically, doffing his long-plumed tricorne—“Les Amours de l’Hermite!”

A crow, black bird of misfortune, flew overhead. For a second I felt the cool flicker of its shadow across my face and, with my fingers, forked the sign against malchance. Tsk-tsk, begone!

The crow seemed unmoved. He fluttered, ungainly, to the head of the well in the courtyard’s center, and I caught an impudent gleam of yellow from his eye. Below him, Lazarillo’s troupe proceeded, undisturbed. The crow cocked his head quickly, greasily, in my direction.

Tsk-tsk, begone! I once saw my mother banish a swarm of wild bees with nothing more than that cantrip; but the crow simply opened his beak at me in silence, exposing a blue sliver of tongue. I suppressed the urge to throw a stone.

Besides, the play was already beginning; an evil cleric wished to seduce a beautiful girl. She took refuge in a convent while her lover, a clown, tried to rescue her, disguised as a nun. They were discovered by the evil suitor, who swore that if he could not have the girl then no one would, only to be foiled by the sudden appearance of a monkey, which leaped onto the villain’s head, allowing the lovers to make good their escape.

The play was indifferent; the players themselves all but exhausted by the heat. Business must have been very bad, I thought, for the players to come to us. An island convent can offer little more than food and board—not even that, if rules are strictly applied. Maybe t

here had been trouble on the mainland. Times were hard for itinerants of all kinds. But Fleur loved the performance, clapping her hands and shouting encouragement to the squealing monkey. Next to her Perette, our youngest novice, looking rather like a monkey herself with her small vivid face and fluffy head, hooted with excitement.

The act was nearing its end. The lovers were reunited. The evil priest was unmasked. I felt slightly dizzy, as if the sun had turned my head, and in that moment I thought I saw someone else behind the players, standing against the light. I knew him at once; there was no mistaking the tilt of his head, or the way he stood, or the long shadow cast against the hard white ground. Knew him, though I saw him for no more than a second: Guy LeMerle, my very own black bird of ill-omen. Then he was gone.

This is how it begins: with the players, LeMerle, and the bird of malchance . Luck turns like the tide, my mother used to say. Maybe it was just our time to turn, as some heretics say the world turns, bringing creeping shadow to the places where once there was light. Maybe it was nothing. But even as the dancers capered and sang, spat fire from reddened lips, smirked from behind their masks, tumbled and rollicked and simpered and stamped the dirt with their gilded feet to the tune of tambour and flute, I seemed to perceive the shadow as it crept closer, covering scarlet petticoats and jingling tambourin, screaming monkey, motley, masks, Isabelle and Scaramouche with its long dark wing. I felt a shiver, even here in the midday sunlight with the whitewashed abbey walls buzzing with heat. The inexorable beginnings of momentum. The slow procession of our Last Days.

I’m not supposed to believe in signs and auguries. All that’s in the past now, with the Théâtre des Cieux. But why see LeMerle, of all people, and after all these years? What could it mean? The shadow across my eyes had already passed and the players were coming to the end of their masque, bowing, sweating, smiling, flinging rose petals over our heads. They had more than earned their board for the night and supplies for their journey.

Beside me, fat Soeur Antoine clapped her meaty hands, her face mottled with exertion. I was suddenly aware of the smell of her sweat, of the dust in my nostrils. Someone clawed my back; it was Soeur Marguerite, her pinched face halfway between pleasure and pain, mouth drawn down in a trembling bow of excitement. The reek of bodies intensified. And from the sisters lined against the heat-crackling walls of the abbey came a cry both shrill and oddly savage, an aiiii! of pleasure and release, as if natural energies, loosened by the heat, had brought a kind of insanity to their applause. Aii! Encore! Aii! Encore!

Then I heard it; a single raised discordant voice, almost lost in a fury of acclamations. Mère Marie, I heard. Reverend Mother is…then once again the distracted buzzing of heat and voices, then the one voice again, higher than the rest.

I looked around for the source of the cry and saw Soeur Alfonsine, the consumptive nun, standing high upon the chapel steps, arms spread, her face white and exalted. Few of the sisters paid her any attention. Lazarillo’s troupe was taking a last bow; the actors went round once more with flowers and bonbons, the fire-eater gave a final spurt of flame; the monkey turned a somersault. Arlequin’s face was running with greasepaint; Isabelle—too old for the part, and with a visible paunch—was melting away in the heat, her scarlet mouth smeared halfway to her ears.

Soeur Alfonsine was still shouting, straining to be heard above the voices of the nuns. “It’s a judgment on us!” I thought she said. “A terrible judgment!”

Now some of the nuns looked exasperated; Alfonsine was never happier than when she was doing penance for something. “For pity’s sake, Alfonsine, what now?”

She fixed us with her martyr’s eyes. “My sisters!” she said, more in accusation than grief. “The Reverend Mother is dead!”

And at those words a silence fell over all of us. The players looked guilty and confused, as if aware that their welcome had been suddenly withdrawn. The tambourin player let his arm drop to his side in a harsh jangle of bells.

“Dead?” As if it could not be real in this iron heat, beneath this sledgehammer sky.

Alfonsine nodded; behind me, Soeur Marguerite was already beginning to keen. Miserere nobis, miserere nobis…

Fleur looked up at me, puzzled, and I caught her in my arms with sudden fierceness. “Is it finished?” she asked me. “Will the monkey dance again?”

I shook my head. “I don’t think so.”

“Why not? Was it the black bird?”

I looked at her, startled. Five years old and she sees everything. Her eyes are like pieces of mirror reflecting the sky—today blue, tomorrow the purple-gray of a storm cloud’s belly. “The black bird,” she repeated impatiently. “He’s gone now.”

I glanced back over my shoulder and saw that she was right. The crow had gone, his message delivered, and I knew then for certain that my premonition was true. Our time in the sunlight had finally come to an end. The masquerade was over.

2

JULY 4TH, 1610

We sent the players into town. They left with an air of hurt reproach, as if we had accused them of something. But it would not have been decent to keep them in the abbey: not in the presence of death. I brought their supplies myself—hay for the horses, bread, goat’s cheese rolled in cinders, and a bottle of good wine, for the sake of traveling theaters everywhere—and bade them good-bye.

Lazarillo gave me a keen look as he turned to go. “You look familiar, ma soeur. Could it be that we have met before?”

“I don’t think so. I’ve been here since I was a child.”

He shrugged. “Too many towns. Faces begin to look the same.”

I knew the feeling, although I did not say so.

“Times are hard, ma soeur. Remember us in your prayers.”

“Always.”

The Reverend Mother was lying on her narrow bed, looking even smaller and more desiccated than she had in life. Her eyes were closed, and Soeur Alfonsine had already replaced her quichenotte with the starched wimple, which the old woman had always refused.

“The quichenotte was good enough for us,” she used to say. “Kiss not, kiss not, we told the English soldiers, and wore the bonnet with the boned lappets to make sure they got the message. Who knows”—and here her eyes would light with sudden mischief—“maybe those English plunderers are hiding here still, and how then would I keep my virtue?”

She had collapsed in the field as she was digging potatoes, so Alfonsine told me. A minute later she was gone.

It was a good death, I tell myself. No pain; no priests; no fuss. And Reverend Mother was seventy-three—an unthinkable age—had already been frail when I joined the convent five years ago. But it was she who first made me welcome here, she who delivered Fleur, and once more, grief surprises me like an unexpected friend. She had seemed immortal, you see: an immovable landmark on this small horizon. Kindly, simple Mère Marie, walking the potato fields with her apron gathered up peasant-fashion over her skirt.

The potatoes were her pride, for though little else grows well in this bitter soil, these fruit are highly prized on the mainland, and their sale—along with that of our salt and the jars of pickled salicorne—ensures us enough revenue to maintain our little independence. That and the tithes bring us a prosperous enough life, even for one who has been used to the freedom of the roads, for at my age it’s time to have done with the dangers and the thrills, and in any case, I remind myself, even with the Théâtre des Cieux there were as many flung stones as sweetmeats, twice as many lean times as good, and as for the drunkards, the gossips, the lechers, the men…Besides, there was Fleur to think of, then as always.

One of my blasphemies—my many, many blasphemies—is the refusal to believe in sin. Conceived in sin, I should have given birth to my daughter in sorrow and contrition; exposed her, perhaps, on a hillside, as our ancestors once abandoned their unwanted young. But Fleur was a joy from the beginning. For her, I wear the red cross of the Bernardines, I work the fields instead of the high rope, I devote my days to a God for wh

om I have little affection and even less understanding. But with her at my side, this life is far from unpleasant. The cloister at least is safe. I have my garden. My books. My friends. Sixty-five of them, a family larger and closer in some ways than any I ever had.

I told them I was a widow. It seemed the simplest solution. A wealthy young widow, now with child, fleeing persecution from a dead husband’s creditors. Jewelry salvaged from the wreck of my caravan at Épinal gave me what I needed to bargain with. My years in the theater served me well—in any case, I was convincing enough for a provincial abbess who had never ventured out of sight of her native coast. And as time passed I realized my subterfuge was unnecessary. Few of us were impelled by holy vocation. We shared little except a need for privacy, a mistrust of men, an instinctive solidarity, which outweighed differences of upbringing and belief. Each one of us fleeing something we could not quite see. As I said, we all have our secrets.

Soeur Marguerite, scrawny as a skinned rabbit and eternally twitching with nerves and anxieties, comes to me for a tisane to banish dreams in which, she says, a man with fiery hands torments her. I brew her tinctures of chamomile and valerian sweetened with honey, she purges herself daily with salt water and castor oil, but I can see from the feverish look in her eyes that the dreams plague her still.

The Evil Seed

The Evil Seed Gentlemen and Players

Gentlemen and Players A Cat, a Hat, and a Piece of String

A Cat, a Hat, and a Piece of String Different Class

Different Class Chocolat

Chocolat Five Quarters of the Orange: A Novel

Five Quarters of the Orange: A Novel A Pocketful of Crows

A Pocketful of Crows Runelight

Runelight Runemarks

Runemarks Jigs & Reels: Stories

Jigs & Reels: Stories Sleep, Pale Sister

Sleep, Pale Sister Holy Fools

Holy Fools The Testament of Loki

The Testament of Loki Peaches for Monsieur Le Curé

Peaches for Monsieur Le Curé Blueeyedboy

Blueeyedboy The Lollipop Shoes

The Lollipop Shoes Coastliners

Coastliners Jigs & Reels

Jigs & Reels Five Quarters of the Orange

Five Quarters of the Orange