- Home

- Joanne Harris

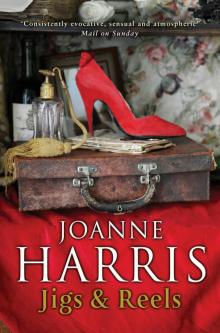

Jigs & Reels: Stories

Jigs & Reels: Stories Read online

About the Book

Take your partners, please.

Suburban witches, defiant old ladies, ageing monsters, suicidal Lottery winners, wolf men, dolphin women and middle-aged manufacturers of erotic leatherwear: in Joanne Harris’s first collection of short stories the miraculous goes hand-in-hand with the mundane, the sour with the sweet, and the beautiful, the grotesque, the seductive and the disturbing are never more than one step away.

This is an eclectic selection of tales for our times that shows a side to Joanne Harris you have never seen before. So go on, be tempted. After all, it’s only dancing.

Contents

About the Book

Title Page

Foreword

Faith and Hope Go Shopping

The Ugly Sister

Gastronomicon

Fule’s Gold

Class of ’81

Hello, Goodbye

Free Spirit

Auto-da-fé

The Spectator

Al and Christine’s World of Leather

Last Train to Dogtown

The G-SUS Gene

A Place in the Sun

Tea with the Birds

Breakfast at Tesco’s

Come in, Mr Lowry, Your Number Is Up!

Waiting for Gandalf

Any Girl Can Be a CandyKiss Girl!

The Little Mermaid

Fish

Never Give a Sucker . . .

Eau de Toilette

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Joanne Harris

Copyright

Jigs & Reels

Joanne Harris

Foreword

It’s wonderful to see that, after a period in the doldrums, the short story has finally made a comeback. A good short story – and there are some very good short stories out there – can stay with you for much longer than a novel. It can startle, ignite, illuminate and move in a way that the longer format cannot. It is often troubling, often frightening or subversive. It provokes questions, whereas most novels tend to try to answer them. Of all the books I have read and loved, I find that it is the short stories I remember most clearly, those vivid, anarchic glimpses into different worlds, different people.

Some of them trouble me, even now. I still worry about what happened to Ray Bradbury’s Pedestrian. I still cry over Roger Zelazny’s ‘Rose for Ecclesiastes’. I still get the shivers when I remember Jerome Bixby’s ‘It’s a Good Life’. And every time I catch the Tube, I feel a sense of unreasonable disquiet, which is largely due to a story called ‘A Subway Named Moebius’, even though I was twelve when I read it, and I cannot even remember the author’s name.

Personally, I find short stories difficult and slow to write. To compress an idea into such a small space, to keep its proportions, to find the voice, is both demanding and frustrating. Four or five thousand words, which might take me a day to write as part of a novel, may take me two weeks to finish as a short story. Like my grandfather’s home-brewed wine, my short stories are mostly experimental in nature. Success is never guaranteed; sometimes a story works, and sometimes it dies on the page, like a very long joke with no punchline, for no reason that I can quite fathom. But I do enjoy them. I enjoy the possibilities; the variety; the challenge. I have been writing them – or trying to – for the past ten years. This is the first time they have been published as a collection.

Faith and Hope Go Shopping

Four years ago, my grandmother went into an old people’s home in Barnsley. Before her death I went there often, and a lot of stories came out of those visits. This is one of them.

IT’S MONDAY, SO it must be rice pudding again. It’s not so much the fact that they’re careful of our teeth, here at the Meadowbank Home, rather a general lack of imagination. As I told Claire the other day, there are lots of things you can eat without having to chew. Oysters. Foie gras. Avocado vinaigrette. Strawberries and cream. Crème brûlée with vanilla and nutmeg. Why then this succession of bland puddings and gummy meats? Claire – the sulky blonde, always chewing a wad of gum – looked at me as if I were mad. Fancy food, they claim, upsets the stomach. God forbid our remaining taste buds should be overstimulated. I saw Hope grinning round the last mouthful of ocean pie, and I knew she’d heard me. Hope may be blind, but she’s no slouch.

Faith and Hope. With names like that we might be sisters. Kelly – that’s the one with the exaggerated lip liner – thinks we’re quaint. Chris sometimes sings to us when he’s cleaning out the rooms. Faith, Hope and Cha-ri-tee! He’s the best of them, I suppose. Cheery and irreverent, he’s always in trouble for talking to us. He wears tight T-shirts and an earring. I tell him that the last thing we want is charity, and that makes him laugh. Hinge and Brackett, he calls us. Butch and Sundance.

I’m not saying it’s a bad place here. It’s just so ordinary – not the comfortable ordinariness of home, with its familiar grime and clutter, but that of waiting rooms and hospitals, a pastel-detergent place with a smell of air freshener and distant bedpans. We don’t get many visits, as a rule. I’m one of the lucky ones; my son Tom calls every fortnight with my magazines and a bunch of chrysanths – the last ones were yellow – and any news he thinks won’t upset me. But he isn’t much of a conversationalist. Are you keeping well, then, Mam? and a comment or two about the garden is about all he can manage, but he means well. As for Hope, she’s been here five years – even longer than me – and she hasn’t had a visitor yet. Last Christmas I gave her a box of my chocolates and told her they were from her daughter in California. She gave me one of her sardonic little smiles. ‘If that’s from Priscilla, sweetheart,’ she said primly, ‘then you’re Ginger Rogers.’ I laughed at that. I’ve been in a wheelchair for twenty years, and the last time I did any dancing was just before men stopped wearing hats.

We manage, though. Hope pushes me around in my chair, and I direct her. Not that there’s much directing to do in here; she can get around just by using the ramps. But the nurses like to see us using our resources. It fits in with their waste not, want not ethic. And, of course, I read to her. Hope loves stories. In fact, she’s the one who started me reading in the first place. We’ve had Wuthering Heights, and Pride and Prejudice, and Doctor Zhivago. There aren’t many books here, but the library van comes round every four weeks, and we send Lucy out to get us something nice. Lucy’s a college student on Work Experience, so she knows what to choose. Hope was furious when she wouldn’t let us have Lolita, though. Lucy thought it wouldn’t suit us.

‘One of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, and you thought he wouldn’t suit us!’ Hope used to be a professor at Cambridge, and still has that imperious twang in her voice sometimes. But I could tell Lucy wasn’t really listening. They get that look – even the brighter ones – that nursery-nurse smile which says I know better. I know better because you’re old. It’s the rice pudding all over again, Hope tells me. Rice pudding for the soul.

If Hope taught me to appreciate literature, it was I who introduced her to magazines. They’ve been my passion for years, fashion glossies and society pages, restaurant reviews and film releases. I started her out on book reviews, slyly taking her off guard with an article here or a fashion page there. We found I had quite a talent for description, and now we wade deliciously together through the pages of bright ephemera, moaning over Cartier diamonds and Chanel lipsticks and lush, impossible clothes. It’s strange, really. When I was young those things really didn’t interest me. I think Hope was more elegant than I was – after all, there were college balls and academy parties and summer picnics on the Backs. Of course now we’re both the same. Nursing-home chic. Things tend to be communal here – some people forget what belongs to them, so there

’s a lot of pilfering. I carry my nicest things with me, in the rack under my wheelchair. I have my money and what’s left of my jewellery hidden in the seat cushion.

I’m not supposed to have money here. There’s nothing to spend it on, and we’re not allowed out unaccompanied. There’s a combination lock on the door, and some people try to slip out with visitors as they leave. Mrs McAllister – ninety-two, spry, and mad as a hatter – keeps escaping. She thinks she’s going home.

It must have been the shoes that began it. Slick, patent, candy-apple red with heels which went on for ever, I found them in one of my magazines and cut out the picture. Sometimes I would bring it out and look at it in private, feeling dizzy and a little foolish, I don’t know why. It wasn’t as if it were a picture of a man, or anything like that. They were only shoes. Hope and I wear the same kind of shoes: lumpy leatherette slip-ons in porridge beige, eminently, indisputably suitable – but in secret we moan over Manolo Blahniks with six-inch perspex heels, or Gina mules in fuchsia suede, or Jimmy Choos in hand-painted silk. It’s absurd, of course. But I wanted those shoes with a fierceness that almost frightened me. I wanted, just once, to step out into the glossy, gleeful pages of one of my magazines. To taste the recipes; see the films; read the books. To me the shoes represented all of that; their cheery, brazen redness; their frankly impossible heels. Shoes made for anything – lolling, lounging, prowling, strutting, flying – anything but walking.

I kept the picture in my purse, occasionally taking it out and unfolding it like a map to secret treasure. It didn’t take Hope long to find out I was hiding something.

‘I know it’s stupid,’ I said. ‘Maybe I’m going peculiar. I’ll probably end up like Mrs Banerjee, wearing ten overcoats and stealing people’s underwear.’

Hope laughed at that. ‘I don’t think so, Faith. I understand you perfectly well.’ She felt on the table in front of her for her teacup. I knew better than to guide her hand. ‘You want to do something unsuitable. I want a copy of Lolita. You want a pair of red shoes. Both are equally unsuitable for people like us.’ She drew a little closer, lowering her voice. ‘Is there an address on the page?’ she asked.

There was. I told her. A Knightsbridge address. It might as well have been Australia.

‘Hey! Butch and Sundance!’ It was cheery Chris, who had come to clean the windows. ‘Planning a heist?’

Hope smiled. ‘No, Christopher,’ she said slyly. ‘An escape.’

We planned it with the furtive cunning of prisoners-of-war. We had one great advantage; the element of surprise. We were not habitual escapees, like Mrs McAllister, but trusties, nicely lucid and safely immobile. There would have to be a diversion, I suggested. Something that would bring the duty nurse away from the desk, leaving the entrance unguarded. Hope took to waiting by the door, listening to the sound of the numbers being pressed on the keypad until she was almost certain she could duplicate the combination. We timed it with the precision of old campaigners. At nine minutes to nine on Friday morning I picked up one of Mr Bannerman’s cigarette butts from the common room and hid it in the paper-filled metal bin in my room. At eight minutes to, Hope and I were in the lobby on our way to the breakfast-room. Ten seconds later, as I’d expected, the sprinkler went off. On our corridor I could hear Mrs McAllister screaming, ‘Fire! Fire!’

Kelly was on duty. Clever Lucy might have remembered to secure the doors. Thick Claire might not have left the desk at all. But Kelly grabbed the nearest fire extinguisher from the wall and ran towards the noise. Hope pushed me towards the door and felt for the keypad. It was seven minutes to nine.

‘Hurry! She’ll be back any moment!’

‘Shh.’ Beep-beep-beep-beep. ‘Got it. I knew one day I’d find a use for those music lessons they gave me as a child.’ The door slid open. We crunched out onto sunlit gravel.

This was where Hope would need my help. No ramps here, in the real world. I tried not to stare, mesmerized, at the sky, at the trees. Tom hadn’t taken me out of the building for over six months.

‘Straight ahead. Turn left. Stop. There’s a pothole in front of us. Take it easy. Left again.’ I remembered a bus stop just in front of the gates. The buses were like clockwork. Five to and twenty-five past the hour. You could hear them from the common room, honking and ratcheting past like cranky pensioners. For a dreadful moment I was convinced the bus stop had gone. There were roadworks where it had once stood; bollards lined the kerb. Then I saw it, fifty yards further down, a temporary bus stop on a shortened metal post. The bus appeared at the brow of the hill.

‘Quick! Full speed ahead!’

Hope reacted quickly. Her legs are long and still muscular; she did ballet as a child. I leaned forwards, clutching my purse tightly, and held out my hand. Behind us I heard a cry; glancing back at the windows of the Meadowbank Home, I saw Kelly at my bedroom window, her mouth open, yelling something. For a second I wasn’t sure the bus would even take an old lady in a wheelchair, but it was the hospital circular, and there was a special ramp. The driver gave us a look of indifference and waved us aboard. Then Hope and I were on the bus, clinging to each other like giddy schoolgirls, laughing. People looked at us, but mostly without suspicion. A little girl smiled at me. I realized how long ago it was since I’d seen anyone young.

We got off at the railway station. With some of the money from the chair cushion I bought two tickets to London. I panicked for a moment when the ticket man asked for my pass, but Hope told him, in her Cambridge professor’s voice, that we would pay the full fare. The ticket man rubbed his head for a minute, then shrugged.

‘Please yourself,’ he said.

The train was long and smelt of coffee and burnt rubber. I guided Hope along the platform to where the guard had let down a ramp.

‘Going down to the smoke, are we, ladies?’ The guard sounded a little like Chris, his cap pushed back cockily from his forehead. ‘Let me take that for you, love,’ he said to Hope, meaning the wheelchair, but Hope shook her head. ‘I can manage, thank you.’

‘Straight up, old girl,’ I told her. I saw the guard noticing Hope’s blind eyes, but he didn’t say anything. I was glad. Neither of us can stand that kind of thing.

The piece of paper with the Knightsbridge address was still in my purse. As we sat in the guard’s van (with coffee and scones brought to us by the cheery guard), I unfolded it again. Hope heard me doing it, and smiled.

‘Is it ridiculous?’ I asked her, looking at the shoes again, shiny and red as Lolita lollies. ‘Are we ridiculous?’

‘Of course we are,’ she answered serenely, sipping her coffee. ‘And isn’t it fun?’

It only took three hours to get down to London. I was expecting much longer, but trains, like everything else, move faster nowadays. We drank coffee again, and talked to the guard (whose name was not Chris, I learned, but Barry), and I described what countryside I could see to Hope while it blurred past at top speed.

‘It’s all right,’ Hope reassured me. ‘You don’t have to do it all now. Just see it first, and we’ll go over it all together, in our own time, when we get back.’

It was nearly lunchtime when we arrived in London. King’s Cross was much bigger than I’d imagined it, all glass and glorious grime. I tried to see it as well as I could, whilst directing Hope through the crowds of people of all colours and ages: for a few moments even Hope seemed disorientated, and we dithered on the platform, wondering where all the porters had gone. Everyone but us seemed to know exactly where they were going, and people with briefcases jostled against the chair as we stood trying to work out where to go. I began to feel some of my courage erode.

‘Oh, Hope,’ I whispered. ‘I’m not sure I can do this any more.’

But Hope was undeterred. ‘Rubbish,’ she said bracingly. ‘There’ll be taxis – over there, where the draught is coming from.’ She pointed to our left, where I did see a sign, high above our heads, which read Way Out. ‘We’ll do what everyone does here. We’ll get a cab. Onwards!’ An

d at that we pushed right through the mass of people on the platform, Hope saying ‘Excuse me’ in her Cambridge voice, me remembering to direct her. I checked my purse again, and Hope chuckled. This time I wasn’t looking at the picture, though. Two hundred and fifty pounds had seemed like inexpressible riches at the Meadowbank Home, but the train fare had taught me that prices, too, had speeded up during our years away from the world. I wondered if we’d have enough.

The taxi driver was surly and reluctant, lifting the chair into the black cab while Hope steadied me. I’m not as slim as I was, and it was almost too much for her, but we managed.

‘How about lunch?’ I suggested, too brightly, to take away the sour taste of the driver’s expression.

Hope nodded. ‘Anywhere that doesn’t do rice pudding,’ she said wryly.

‘Is Fortnum and Mason’s still there?’ I asked the driver.

‘Yes, darling, and the British Museum,’ he said, revving his engine impatiently. ‘Best place for you two,’ I thought I heard him mutter. Unexpectedly, Hope chuckled. ‘Maybe we’ll go there next,’ she suggested meekly. That set me off as well. The driver gave us both a suspicious glance and set off, still muttering.

There are some places which can survive anything. Fortnum’s is one of these, a little antechamber of heaven, glittering with sunken treasures. When all civilizations have collapsed, Fortnum’s will still be there, with its genteel doormen and glass chandeliers, the last, untouchable, legendary defender of the faith. We entered on the first floor, through mountains of chocolates and cohorts of candied fruits. The air was cool and creamy with vanilla and allspice and peach. Hope turned her head gently from side to side, breathing in the perfume. There were truffles and caviar and foie gras in tiny tins and giant demijohns of green plums in aged brandy and cherries the colour of my Knightsbridge shoes. There were quails’ eggs and nougatines and langues de chat in rice-paper packets and champagne bottles in gleaming battalions. We took the lift to the top floor and the café, where Hope and I drank Earl Grey from china cups, remembering the Meadowbank Home’s plastic tea service and giggling. I ordered recklessly for both of us, trying not to think of my diminishing savings: smoked salmon and scrambled eggs on muffins light as puffs of air, tiny canapés of rolled anchovy and sundried tomatoes, Parma ham with slices of pink melon, apricot and chocolate parfait like a delicate caress. ‘If Heaven is anything like as nice as this,’ murmured Hope, ‘send me there right now.’

The Evil Seed

The Evil Seed Gentlemen and Players

Gentlemen and Players A Cat, a Hat, and a Piece of String

A Cat, a Hat, and a Piece of String Different Class

Different Class Chocolat

Chocolat Five Quarters of the Orange: A Novel

Five Quarters of the Orange: A Novel A Pocketful of Crows

A Pocketful of Crows Runelight

Runelight Runemarks

Runemarks Jigs & Reels: Stories

Jigs & Reels: Stories Sleep, Pale Sister

Sleep, Pale Sister Holy Fools

Holy Fools The Testament of Loki

The Testament of Loki Peaches for Monsieur Le Curé

Peaches for Monsieur Le Curé Blueeyedboy

Blueeyedboy The Lollipop Shoes

The Lollipop Shoes Coastliners

Coastliners Jigs & Reels

Jigs & Reels Five Quarters of the Orange

Five Quarters of the Orange