- Home

- Joanne Harris

The Evil Seed

The Evil Seed Read online

About the Book

‘I’m still rather fond of this first book of mine, in spite of all the time that has elapsed, and in spite of the way my style has evolved.’ Joanne Harris

Caution – May contain vampires.

It’s never easy to face the fact that a man you once loved passionately has found the girl of his dreams, as Alice discovers when Joe introduces her to his new girlfriend. Then Alice finds an old diary and reads about two men and the mysterious woman who bewitched them both, buried in Grantchester churchyard half a century ago.

As the stories seem to intertwine, Alice comes to realize that her instinctive hatred of Joe’s new girlfriend may not just be due to jealousy, as she is plunged into a nightmare world of obsession, revenge, seduction – and blood.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Part One: The Beggar Maid

Introduction

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Three

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Part Two: The Blessed Damozel

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter One

Part Three: Death and the Maiden

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Two

Chapter Two

Chapter Two

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Part Four: Beata Virginia

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Two

Chapter One

Chapter One/Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Epilogue

About the Author

Also by Joanne Harris

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all those who contributed to bringing this book back from the dead. To my editor Francesca Liversidge, to Lucie Jordan and Lucy Pinney, to Holly Macdonald who did the artwork. To my heroic agent Peter Robinson, to Jennifer and Penny Luithlen and, as always, to the book reps, book sellers and enthusiasts who work to tirelessly to keep my books on the shelves. Thanks also to the many readers who persisted in asking for the reissue of this book. It wouldn’t be here without you.

Author’s Note

There are dangers in trying to dig up the past. There must be rewards as well, I daresay, but as a child it was always the dangers that appealed most to my imagination: the curse of the pharaoh’s tomb, the artefacts removed, in the face of ancient warnings, from the ruined Mayan temple, bringing catastrophe in their wake; the lost city guarded by the ghosts of the dead. Perhaps, then, it was inevitable that this book, written so many years ago that I had thought it safely buried, should haunt me so persistently, clamouring for release, just as so many of my more avid and curious readers have clamoured for its re-publication.

A little background, then. First, let me say that it was never my intention to bury this book. Time does that pretty well on its own; and I was twenty-three when I wrote it. That makes this seed a good twenty years old, and when it was first planted, I had no idea of what it might one day blossom into.

I was a trainee teacher a few years out of Cambridge, living with my boyfriend (later to become my husband) in a mining village near Barnsley. We had seven cats, no central heating, no real furniture except for a bed, a drum kit and a couple of MFI bookcases, and my computer was an unwieldy thing with only five hundred bytes of RAM, which had an unpleasant mind of its own and a definite tendency to sulk. The neighbours referred to us as Them Hippies because I had decorated our walls with psychedelic murals, painted in acrylics and oils on to the Anaglypta. I made the patchwork curtains myself, as well as re-grouting the bathroom. My study was an upstairs bedroom, a kind of eyrie from which I could see the whole village: terrace houses, cobbled streets, back yards, distant fields. It always seemed to be foggy. I drove an ancient, bad-tempered Vauxhall Viva called Christine (after the Stephen King novel), which broke down on a weekly basis. Looking back now, I don’t even know how I found the courage to write. It was freezing cold in my study; I had a little gas heater that threw out toxic fumes, and some multicoloured fingerless gloves. Maybe I thought it was romantic. My previous attempt at a novel, Witchlight, had been rejected by numerous publishers. I believe my pig-headed, awkward side (which is still the strongest part of me) took this as a kind of challenge. In any case, I began writing The Evil Seed – what my mother came to call That Terrible Book – and the idea slowly gained momentum, was galvanized into a kind of life and finally attracted the attention of a reader employed by a literary agency, which ultimately took me on.

Of course, I had no idea of what I was doing. I had no experience of the literary world, no contacts, no friends in the business. I had never studied creative writing, or even joined a writers’ group. I didn’t have a long-term plan; I didn’t expect to make money. I was simply playing Can You? – that game that all storytellers play, following the skein of cherry-coloured twist along the crooked path through the woods to find out where it leads them.

For me, it was Cambridge – partly because I knew the place, and it seemed like the ideal setting for the kind of ghost story I wanted to write. I’d had the idea originally when I was just a student. On a visit to Grantchester, I happened to look in the cemetery and saw an interesting gravestone, bearing the inscription: Something inside me remembers and will not forget. That phrase, and the odd open-door shape of the monument, sparked off the beginnings of this story. My plot was ambitious; my style experimental. I was still too young to have quite found my voice, and so I wrote in two voices: one, that of a middle-aged man, Daniel Holmes, the other as a more conventional third-person narrator. I headed all the chapters, One and Two alternately, to distinguish between the two time frames; one being the present day, the other being just after the Second World War. I made it a story about vampires without ever using the word itself; a ghost story without a ghost; a horror story in which the mundane turns out to be more unsettling than any mythology. But it wasn’t just a horror tale. It was also about seduction; about lost friendship, about art and madness and love and betrayal. I chose quite an ambitious structure – rather too ambitious for a horror novel. But I didn’t think of what I was writing as genre fiction at all. I was trying to recreate the atmosphere of a nineteenth-century Gothic novel in a modern environment and a literary style. My publishers wanted the next Anne Rice. I should have known that would cause trouble.

The book came out some years later, under a somewhat gruesome black jacket. I’d wanted to call it Remember, but had been persuaded to change the name because my editor felt that it sounded too much like a romance. I never felt sure of the new name. Still, there’s nothing to beat the feeling of seeing your first book in print. I used to lurk in bookshops

, trying to spot someone buying my book, occasionally removing copies from the horror section and putting them into literature.

It wasn’t literature, of course. It was a piece of fairly juvenile writing from someone who yet had to find her own style. At best, it was a heroic failure. At worst, it was pretentious and over-written. For a long time I resisted the demands of my readers to see it back in print – out of superstition, perhaps; my version of the mummy’s curse. But given the chance to revisit this particular ruined temple, I have found it strangely rewarding. Heroic failure though it may be, I’m still rather fond of this first book of mine, in spite of all the time that has elapsed and in spite of the way my style has evolved. There’s something in there that still resonates, something I had thought dead and buried, but which has come quite readily back to life. I’m not sure what my readers will make of it. Students of creative writing may use it as a means of charting the progress of one author over twenty years of trial and error. Others will just read the story for what it is, and, hopefully, may enjoy it.

The editor in me has made a few changes – only a few, I promise you – the story remains completely intact, but I couldn’t resist brushing away some of the cobwebs that have gathered in the passageways. Even so, you should read the inscription over the door before you decide to follow me in. It’s written in Latin (or maybe in hieroglyphics). It reads, roughly translated:

Caution – May Contain Vampires.

There. You can come in now.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

PART ONE

The Beggar Maid

Introduction

Larger than life, face and hands startlingly pale in a canvas as dark and narrow as a coffin, eyes fathomless as the Underworld and lips touched with blood, Proserpine seems to watch some object beyond the canvas in a mournful reverie. She holds the orb of the pomegranate, forgotten, against her breast, its golden perfection marred by the slash of crimson which bisects it, indicating that she has eaten, and thereby forfeited her soul. Doomed to remain for half the year in the Underworld, she broods, watching for the reflections of the far-away sun which flicker on the ivy-crusted walls.

Or so we are led to believe.

But she is a woman of many faces, this Queen of the Underworld; therein lies her power and her glamour. Pale as incense she stands, and the square of light which frames her face does not touch her skin; she shines with her own lambency, her pose weary as the ages, yet filled with the strength of her invulnerability. Her eyes never meet yours, and yet they never cease to fix a certain point just beyond your left shoulder; some other man, perhaps, doomed to the terrible bliss of her love, some other chosen man. The fruit she holds is red as her lips, red as a heart at its centre. And who knows what appetites, what ecstasies lie within that crimson flesh? What unearthly delights wait in those seeds to be born?

From The Blessed Damozel, Daniel Holmes

Prologue

There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance;

pray you, love, remember.

Hamlet, 4.5

WHEN I WAS a child, I had a lot of toys; my parents were rich and could afford them, I suppose, even in those days, but the one which I always remembered was the train. Not a clockwork train, or even one of those which you can pull behind you, but the real thing, speeding through countryside of its own, trailing a plume of white steam behind it, racing faster and faster towards a destination which always seemed to elude it. It was a spinning-top, painted red on the bottom half and made of a kind of clear celluloid on top, beneath which a whole world glowed and spun like a jewel, little hedges and houses and the edge of a painted circle of sky so clean and blue that it nearly hurt you to look at it too long. But best of all when you pumped the little handle (‘always be careful with that handle, Danny, never spin your top too hard’), the train would come puffing bravely into view, like a dragon trapped under glass and shrunk by magic to minuscule size; coming slowly at first, then faster and faster until houses and trees blurred into nothingness around it, the whine of the top lost in the triumphant scream of the engine-whistle, as if the little train were singing with the fierce joy of being so nearly there.

Mother, of course, said that to spin the top too hard might break it (and I always took care, just in case that might be true). But I think I believed, even then, that one day, if I was careless, if I let my attention wander even for a moment, then the train might finally reach its mysterious, impossible destination like a snake eating itself, tail first, and come bursting, monstrous, into the real world, all fires blazing, steel throwing sparks into the quiet of the playroom, to come for me in revenge at its long imprisonment. And maybe some of my pleasure was knowing that I had it trapped, that it could never escape because I was too careful, and that I could watch it when I liked. Its sky, its hedges, its mad race through the world were all mine, to set into motion when I liked, to stop when I liked, because I was careful, because I was clever.

But then again, maybe not. I don’t recall being a fanciful child. I was certainly not morbid. Rosemary did that to me – did it to all of us, I suppose. She made us all into children again, looming over us like the wicked witch in the gingerbread house, ourselves little gingerbread men running around in circles, like little trains under celluloid as she watched and smiled and pumped the handle to set her wheels in motion.

My mind is wandering; a bad sign, like the lines around my eyes and the thin patch at the top of my head. There again, Rosemary’s doing. When the priest said, ‘Dust to dust’, I looked up and thought I saw her again, just for a moment, leaning against the hawthorn tree with a smile in her eyes. If she had looked at me, I think I would have screamed. But she looked at Robert instead.

Robert was white, his face hollow and haunted beneath his hat, but not because he saw her. I was the only one who saw her, and only for a moment; a change in the light, a movement, and I would probably have missed her. But I didn’t. I saw her. And that, more than anything, is why I am writing to you now, to you, to my future beyond the grave, to tell you about myself and Robert and Rosemary … yes, Rosemary. Because she still remembers, you see. Rosemary remembers.

One

IT WAS A beautiful day, crisp and autumn-clear, the ground bright with leaves, and the sky as round and as blue as the sky beneath which the little train had raced so many years ago. There were not many people: myself, Robert, a handful of others, all in black, their faces a blur in the sunlight. Only Robert’s stands out in my memory, pale and caricatured by grief. It hurt me to look at him.

‘White flowers only’, had said the advertisement in the Cambridge News and that day there were hundreds of them: lilies and roses and great shaggy overblown chrysanthemums, lining the grave and the grassy path and crowning the coffin as it was lowered into the ground. Their scent was overwhelming, but the dark smell from the grave was stronger, and as the priest spoke the final words of the service I backed away from that open hole as a man retreats from the side of a cliff, feeling wretched for my friend but also strangely light-headed. Maybe it was the flowers.

He had chosen a lovely plot for her: right at the back of the churchyard, up against the wall, beneath the combined branches of a hawthorn tree and a shady yew. The death-tree stood arm-in-arm with the life-tree, their bright berries seeming to mock the grief of the mourner, as if they had been in league with the sweetness of the day to bedeck themselves in their most joyful colours to celebrate her passing. It would be beautiful in summer, I thought to myself, shady and green and silent. This year, the hemlock and the tall weeds had been cleared away for the funeral but they would grow back.

Grow back.

The thought disturbed me in some way, but I could not think why. Let them grow, after all, let them invade that quiet place, overgrow the grave and the stone and the memory of Rosemary for ever; let flowers grow from her blind eyes. If only this could be the end, I thought. If only she could be forgotten. But Robert would remember, of course. After all, he loved her.

&n

bsp; It was in the spring of 1947 when Rosemary first entered our lives. I was passing the weir at Magdalene Bridge, on my way to meet Robert at a tea-shop before we went to the library. I was twenty-five, a graduate student at the university; I was writing a doctorate paper on the Pre-Raphaelites (a much-maligned school of painting at the time, which I hoped to bring back into fashion). I existed in a world of books and absolutes; which suited my withdrawn, and somewhat obsessive personality. The stones and cobbles of Cambridge rested quiet, as they had done for centuries, an ideal backdrop for my studies and a retreat for myself from the bewildering advances of the modern world. I lived in the past and was happy there.

I had one good friend, a very nice lodging by Grantchester way and a comfortable allowance from my father, which supplemented my grant from the faculty. I had always assumed that when my doctorate was finished I would join the university as a full-time lecturer perhaps staying on at Pembroke, where my tutor, Doctor Shakeshafte, had always had high hopes for me. My life was all planned out as neatly and precisely as the gardens and lawns of Cambridge, and it never occurred to me to question the plan, or to hope for something more.

On that particular day, with the bright morning sun reflecting great panels of gold from the mullioned windows of Magdalene College, I was feeling on top of the world. As I quickened my step on the bridge, I was just beginning to sing to myself when I heard a sound below me and stopped.

I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I had ignored the sound, if I had run across the bridge for dear life without looking back, but there was no question of that of course. She had it all too well planned out. You see, it was the sound, unmistakably, of something falling into the river.

It was spring, and the Cam was at its highest. The weir rushed and snarled less than a hundred yards away, and anyone who fell in at that point was likely to be caught in the sluice and drowned. That was why punting was forbidden beyond the bridge; not that anyone would have been fool enough to try it. For a moment I was still, squinting over the parapet for the log or the broken punt or the piece of floating debris which must have caused the sound; then I saw her, a pale blur of a face over some kind of a pale dress ballooning out around her, hollows for eyes, every feature a blur, as if she were already a ghost.

The Evil Seed

The Evil Seed Gentlemen and Players

Gentlemen and Players A Cat, a Hat, and a Piece of String

A Cat, a Hat, and a Piece of String Different Class

Different Class Chocolat

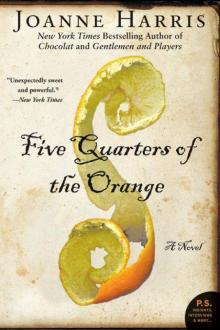

Chocolat Five Quarters of the Orange: A Novel

Five Quarters of the Orange: A Novel A Pocketful of Crows

A Pocketful of Crows Runelight

Runelight Runemarks

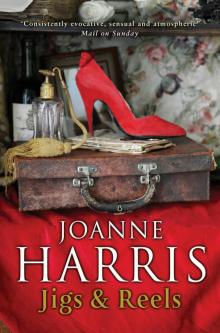

Runemarks Jigs & Reels: Stories

Jigs & Reels: Stories Sleep, Pale Sister

Sleep, Pale Sister Holy Fools

Holy Fools The Testament of Loki

The Testament of Loki Peaches for Monsieur Le Curé

Peaches for Monsieur Le Curé Blueeyedboy

Blueeyedboy The Lollipop Shoes

The Lollipop Shoes Coastliners

Coastliners Jigs & Reels

Jigs & Reels Five Quarters of the Orange

Five Quarters of the Orange